The boy, the girl, and the five-month drenching...

On 31st August 2022, my wife and I jumped on a one-way flight to Perth, the capital of Western Australia.

Being from London, I have always associated Australia with sun-drenched beaches, the Great Barrier Reef, cold beers, the Outback, Uluru and surfing. I had decided (with my wife’s blessing) that the best way for us to see it, in all its sun-kissed glory, would be to drive a small camper van from Perth on the West Coast to Brisbane on the East Coast - a journey of several thousand miles.

Our timing was perfect also, or so I thought, with September signalling the arrival of spring. We would be driving into the famously warm Australian summer, and we packed appropriately, bringing one jumper and a light jacket each.

After allowing ourselves a few days to get over the jetlag, we picked up our van and started to drive. It took about five days to reach the Southwestern tip of Australia, before we turned east, keeping the ocean on our right, and cruising towards the promise of sandy shores.

Morning jog from our campground to the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse.

The Lighthouse marks the Southwestern tip of mainland Australia, where the Southern and Indian Oceans meet!

Things started to go wrong pretty quickly. Putting to one side an occasional few days of sunshine, the weather over the next two months was horrendous. It was cold, grey, and it was constantly pouring with rain, sometimes so heavily that we had to spend the whole day hiding in our tiny van – which did not turn out to be as tightly weatherproofed as we might have hoped. Storm after storm shook the van from side to side at night, and any time we turned up at a nice beach, so, it seemed, did the rain.

After yet another exhausting day of abandoned plans, soaked clothes and damp air, I settled down in the van to do some research. I did not understand how the weather, in Australia of all places, could be so extraordinarily wet and miserable.

And that was how I came to learn about The Boy, and The Girl.

…

In the 1600s, fishermen in South America started to notice periods of unusually warm water in the Pacific Ocean. These periods of warmer water appeared cyclically, normally peaking around December. They named this phenomenon “El Niño de Navidad”, which broadly translates as “The Boy of Christmas”.

Between “El Niño” events, the fishermen noticed that, periodically, the Pacific Ocean was colder than normal. They named these periods “La Niña” or “The Girl”, the opposite of the “El Niño” occurrence.

Today, we understand El Niño and La Nina as the two parts of what scientists call the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. In a ‘normal’ year, the world does not experience a La Nina or El Niño event, which is to say that neither of these phenomena occurs.

El Niño and La Niña events generally occur every two to seven years, on average, albeit they do not occur on a regular schedule. Generally, El Niño occurs more frequently than La Niña, and whilst they can last for several years, both generally last around nine to 12 months.

El Niño and La Niña are caused by changes in air pressure over the equatorial Pacific, which in turn impacts the strength of the prevailing winds which typically blow from east to west across the Pacific Ocean.

During El Niño, changes in pressure cause these winds to drop (or even change direction). Less wind means that less of the water on the surface of the Pacific Ocean is moved from east to west. This broadly stationary body of water is warmed by the sun more than usual, and less cold water than is normal rises from the deep ocean to replace that which has moved west, hence the warmer temperatures observed by the South American fishermen.

During La Niña, the changes in pressure cause the winds to strengthen. This causes more water to be pushed west than is usual, and more cold water than is normal rises from deep in the Pacific Ocean to replace it – hence the colder temperatures observed by the fishermen.

These huge bodies of warmer and colder water have a range of impacts on the atmosphere. In particular, they can cause the jet streams to move north (La Niña) and south (El Niño). This shift in the jet streams, in turn, has a number of impacts on the weather around the world.

An El Niño year will typically be associated with wetter and colder conditions in Southern parts of the United States and warmer conditions in Northern parts of the US and Canada. El Niño can also create hotter and drier conditions in Asia, Australasia, the Indian subcontinent, parts of Africa and South America.

A La Niña year is typically associated with the opposite; Southern parts of the US tend to be warmer and drier, whilst Northern parts of the US and Canada are wetter and colder. La Niña tends to create colder and wetter conditions in Australasia and parts of Asia.

…

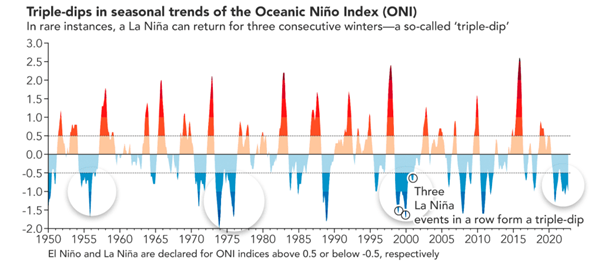

It turned out, to my dismay, that between 2020 – 2023, the world was experiencing a rare ‘triple-dip’ La Niña, i.e. three consecutive La Niña years. Whilst this has happened before, most recently between 1973-76 and then in 1998-2001, both of these events had been preceded by a strong El Niño. This one was not, and scientists are still trying to understand what caused it to occur.

Image Credit: NASA

Having already experienced two La Niña years, Australia was already fairly damp before my wife and I arrived. As unprecedented amounts of rain continued to fall across huge parts of the country, rivers everywhere burst their banks and flooding was rife. Almost everywhere that we went we saw the impact of floods and landslides. We arrived in Melbourne at the same time as what the news called a “rain bomb” which promptly closed the ferry terminal in Tasmania cancelling that part of our trip, and the wild weather showed little sign of abating when we finally boarded a flight from Brisbane to Auckland several weeks later (delayed for three hours by – a rainstorm).

1,500 miles later from Brisbane to Auckland, New Zealand, across the Tasman Sea, the situation was no different. Having booked a new camper van several months in advance, we now found ourselves stuck on the North Island of New Zealand, for what locals described as the wettest summer on the North Island since the 1970s (during the triple-dip La Niña that occurred from 1973-76).

Our tour of the North Island took us to the city of Napier at one point, where we stayed with our friends Graeme and Kat, and their two wonderful kids. In a particularly sobering moment about a week after we left them, Kat’s parents lost their home and orchards in a town nearby to flooding, as Cyclone Gabrielle dropped huge volumes of rain on already saturated ground. They had been in that house for 40 years and had never previously been impacted by floodwaters.

Kat’s parent’s home, with a before and after image showing the impact of the flooding.

In the first image you can see the dark silt from the floodwaters on top of the roof, indicating how high the waters rose.

Whilst El Niño and La Niña events are not new, the data does make clear that the severity of their impacts is being significantly increased by climate change.

At the end of the latest triple-dip La Niña the world immediately swung back to a strong El Niño, and 2023 went on to break an unfortunate range of records on the temperature scale. The final part of our travels took my wife and I to the US and Canada, where the impact of the extraordinary heat across Canada, stoked by the El Niño event, caused wildfires in hundreds of places around the country, blanketing large chunks of the United States and Canada with smoke. At one point we drove through a section of British Columbia which was dealing with several active fires. The scenes were like something out of a zombie movie, with visibility reduced to just a hundred or so meters at the worst points.

Driving through active wildfire zones in British Columbia.

The mountains in the background of this image are almost totally obscured by smoke.

It is hard to think of a country that we visited during our year away which was not obviously suffering from extreme weather. Between the drenching that we experienced in Australia and on the North Island of New Zealand, the unusually intense heat that we experienced in parts of Asia and the wildfires raging throughout Canada, it was hard not to see, and experience, the impacts of La Niña and El Niño, exacerbated by climate change, everywhere that we went.

…

The increasing intensity of El Niño and La Niña events is important for businesses to understand. A range of issues are thrown up by these weather phenomena which everyone involved in risk management and business strategy needs to be aware of. Here are a few:

– Agriculture – The droughts and extreme rainfall caused by ENSO events in different parts of the world have a significant impact on food production. The 2020-23 La Niña had a range of impacts on agriculture and the prices of basic foodstuffs, including wheat, corn and soybeans, from regions around the world.

– Shipping – The lack of rainfall caused by ENSO events can exacerbate problems caused by a lack of water in the world’s main trade canals, particularly the Panama Canal, which saw extensive traffic disruption in 2023 as El Niño caused water levels to drop. More generally severe weather events, including storms in the Pacific Ocean, cause damage to shipping infrastructure or require ships to re-route to avoid dangerous ocean conditions, all of which cause costly delays.

– Impacts on employees – ENSO events cause extreme and prolonged heat in many places around the world. Many of these regions are not well set up to deal with the heat, and employees find themselves working in places without adequate (or any) air conditioning. This can significantly impact productivity, or even make work environments unsafe. Where air-conditioning is widely used, the huge increase in demand on the electrical grid can cause blackouts or other capacity issues. In Texas, for example, power prices surged 80% during one week in June 2023 as a heat wave put added strain on the grid.

– Insurance – As more frequent and increasingly intense extreme weather events cause ever greater damage (2023 is likely to be the third year in a row where climate change-related losses have exceeded over $110 billion in damages), insurance premiums are likely to increase for businesses across the board.

– Wildfires – The unusually hot and dry conditions brought about by ENSO events can exacerbate and intensify wildfires around the world. The recent fires in Canada, which blanketed much of the Northern United States in smoke, occurred as Canada felt the additional heat from the current El Niño event. Similarly, an unusually warm and dry spring in Australia (again, exacerbated by El Niño) has already resulted in numerous serious wildfires. These fires cause a range of disruptions, and smoke from wildfires can pose a serious health risk.

– Cost – According to Bloomberg Economics modelling, previous El Niño events resulted in a marked impact on global inflation, adding 3.9 percentage points to non-energy commodity prices and 3.5 points to oil. Businesses need to factor the impacts of these conditions into their financial modelling and projections and may need to manage market expectations appropriately as ENSO events develop and progress – particularly where they last longer than the usual nine to 12 months.

Whilst ENSO events are a normal part of global weather patterns, the data does make clear that, at the very least, their impacts are being exacerbated by climate change. All businesses need to take The Boy and The Girl into careful consideration when planning their business continuity, risk management and ESG strategies, each of which should account for how ENSO events can impact business operations.

Legal teams should also be aware of these phenomena, as business impacts resulting from El Niño and La Niña events will continue to throw up a range of legal issues, covering the spectrum of insurance, litigation following from loss or other delay, employment, health and safety and beyond.

…

I often find myself thinking back to those South American fishermen in the 1600s. I think about how different the world must have looked when they first observed “El Niño de Navidad”. At the time the global population was about 500 million people. The beginning of the Industrial Revolution was over 150 years away, some 30 million bison roamed the Americas and global shipping was powered by little more than the wind and oars. The oceans that those fishermen relied upon were abundant with life and there was no such thing as plastic pollution.

I wonder what they might think if they could see the planet today. I wonder if they might still name the phenomena that they observed something as innocent as The Boy and The Girl.

Get in touch

We opened our doors on 4 March 2024. As a relatively new firm, we are not yet in a position to offer all of the services described on this website. We have done our best to make clear what we can do now, and what forms part of our exciting plans for the years ahead. We are working hard to make our ambitious vision into a reality.

In the meantime, please do subscribe to receive our regular thought leadership and feel free to follow our journey and progress on LinkedIn.